Trial Magazine

Theme Article

Mindfulness and Well-being

Trial lawyers are well prepared to represent their clients but are not always well trained to care for themselves. To perform optimally, and maintain health and well-being, consider practicing mindfulness.

March 2018How ironic it is that many of the qualities that make us great lawyers can be toxic to us as human beings. Our well-developed ability to imagine all possible negative outcomes, look for fault, assign blame, advocate vigorously for our positions, and work amid conflict and uncertainty are only a few of the reasons our legal training has been linked to high levels of stress, depression, and anxiety.1 These skills, strengthened and rewarded over years of legal practice, also can interfere with our well-being and ability to relax and feel optimistic.

Compare lawyers to professional athletes, who also engage in work that is intense, fast-paced, competitive, and filled with uncertain outcomes.2 Professional athletes receive significant training and practice in both the primary skills required for their sport and the “secondary competencies” such as focus, resilience, self-regulation, and endurance.3 Their average career span is seven years, most of which is spent practicing rather than competing, and includes regular off-season time to rest.4

Lawyers, by contrast, often plan for a career span of 45 years or more, perform on demand eight or more hours a day, may struggle to get a few weeks of vacation a year, and have little or no training in these essential secondary competencies.

Trial lawyers in particular live daily with the possibilities of being opposed, denied, overruled, or dismissed, and they often face an opponent whose job is to prove them wrong. For those who work with the underserved, children, families, and issues of life and death, secondary trauma and empathy fatigue are occupational hazards.5 It should be no surprise that lawyers have higher rates of problematic drinking than other professionals—it affects more than one in three lawyers.6 Without proactively cultivating capabilities to engage in law practice in a sustainable and healthy way, we can’t perform at our best or without cost to ourselves and others.

I experienced this firsthand for 17 years as a lawyer in a large firm, where I enjoyed my work and achieved success. However, I also avoided addressing the exhaustion, worrying, and physical symptoms that became part of my everyday reality. Then, at 40, with a 3-year-old child, I was diagnosed with colon cancer and underwent major surgery and seven months of weekly chemotherapy. I finally had to acknowledge that if I wanted my life and career to be sustainable and satisfying, I had to find a new way to be.

You likely know the feeling of being out of balance. We all experience symptoms of stress from time to time, but when “every so often” becomes “most of the time,” something is amiss. It’s been more than 15 years since my recovery and choice to leave my law career to help lawyers and other professionals address issues of wellness and sustainability. That’s where the practice of mindfulness comes in.

What Is Mindfulness?

Mindfulness is often defined as paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally. Strengthening our innate capacity to bring this quality of awareness into our lives has been proven to reduce stress and have profound benefits for our physical and mental health and well-being.7 Mindfulness is a foundation for developing professional competencies, including focus, self-regulation, and resilience, and it allows us to relate in new and more skillful ways to whatever arises in life moment to moment.

Researchers have documented that mindfulness supports tissue growth in the hippocampus, an area of the brain responsible for learning, memory, and resilience.8 It supports activity in the prefrontal cortex, including planning, attention, decision-making, problem solving, and memory.9 Mindfulness practice also is correlated with a decrease in the reactivity of the amygdala, the portion of the brain associated with stress and the fight/flight/freeze response.10

47% of our waking hours are spent thinking about something other than what is actually happening.

It's Simple but Not Easy

Have you ever driven somewhere, parked your car, and realized that you had little or no memory of what appeared along the way? Or have you been reading and become so distracted that you had to reread pages? You are not alone. A Harvard University study concluded that nearly 47 percent of our waking hours are spent thinking about something other than what is actually happening.11 This has enormous implications for the quality of our work, as well as the quality of our lives.12

Mindfulness can be an antidote to this state of “continuous partial attention.”13 Improving the quality of our attention is simple but not easy. As soon as you try to pay attention in this way, you will notice that your mind has a mind of its own. We spend an inordinate amount of time in the past and future, caught up in worrying, planning, remembering, regretting, and just daydreaming. We spend much less time experiencing the present moment directly—in other words, being mindful.

You also will likely notice that we are constantly judging—ourselves, others, and our experiences. We perceive the world through filters of conditioning and habit that may lead us to act in unhealthy ways. By practicing mindfulness, we can become more comfortable with what is, and we create space for conscious, life-affirming choices. If you want to receive the benefits of mindfulness, you need to practice. You are not trying to make anything happen while practicing; you are just showing up. If your mind feels busy, remember that mindfulness is not about having a quiet mind but rather about noticing that you have become distracted and bringing your mind back to your focus.

Create a clearing. There are many ways to practice mindfulness. Most involve paying attention to something and, as soon as you notice you have gotten distracted or your mind has wandered, returning your focus to the intended object of your attention. Because your breath and body are always in the present moment no matter where your mind has drifted, they are a useful focus for mindfulness practice. Try the “body scan” exercise.

Body Scan

In body scan meditation, you methodically bring your attention to your body, moving from the feet to the head or the head to the feet. You may notice a wide range of physical feelings: pressure, lightness, tingles, pulsation, itches, aches, discomfort, warmth, coolness, and more. You may not notice anything. The intention is not to elicit relaxation but to cultivate awareness—to simply notice what is there to be noticed. You might notice thoughts or emotions as well as you move through the scan. There is no need to analyze or change your body in any way—just feel and acknowledge whatever is present. Notice how this practice strengthens the ability to aim, sustain, and redirect focus.

The more regularly you practice the body scan, the easier and more natural it will be to check in with your body with precise and concentrated attention during the day. When you notice tension in specific regions, bring nonjudgmental awareness to the sensation and experience how the sensation may change.

Practicing regularly may not feel comfortable or easy, and it is best to start by picking a length of time that is feasible for you. In our culture of relentless “doing,” we’re not used to just “being.” Creating new habits takes some courage and patience, but the brain can change and create new neural connections in response to new behavior.

Short moments many times a day. Another way to practice mindfulness is to begin paying attention in new ways to what you are already doing as you are doing it. Choose something you do every day, and use it to strengthen your ability to sustain focused attention. Examples include becoming fully present when you walk up or down stairs, take the first few bites of a meal or sips of a beverage, or turn on your computer in the morning and shut it down at the end of the day. Each time you bring focused awareness to a task, you are strengthening the muscle of mindfulness.

Move from reacting to responding. When faced with an unpleasant or unwanted situation, we may experience stress reactivity. Our reactions include physical sensations, thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that are, more often than not, automatic and habitual. Once these reactions are triggered, we may act in ways that we regret later, as the part of the brain responsible for complex thinking and emotional self-regulation is taken over by the part that is focused on surviving a perceived threat. The more quickly we can recognize signals of stress and imbalance, the more skillfully we can intervene in the stress cycle, make good choices, and maintain our own health and well-being.

Unfortunately, many of us live in a moderate stress reaction on a daily basis. It is important to understand that a stress reaction can be triggered to some degree by anything that threatens our sense of well-being—challenges to social status, ego, or strongly held beliefs—or our desire to control things.14 Common workplace stress triggers include not feeling respected, appreciated, or listened to; being treated unfairly; and being held to unrealistic deadlines.15

Noticing what is arising externally or internally is a first step in choosing how best to meet it. Without awareness, we don’t have a choice in how we think or behave. When someone cuts you off in traffic, do you generally pause to consider the best way to respond, or do you speak or gesture immediately and automatically? When someone says something hurtful or critical, have you ever reacted immediately in a way that you later regretted?

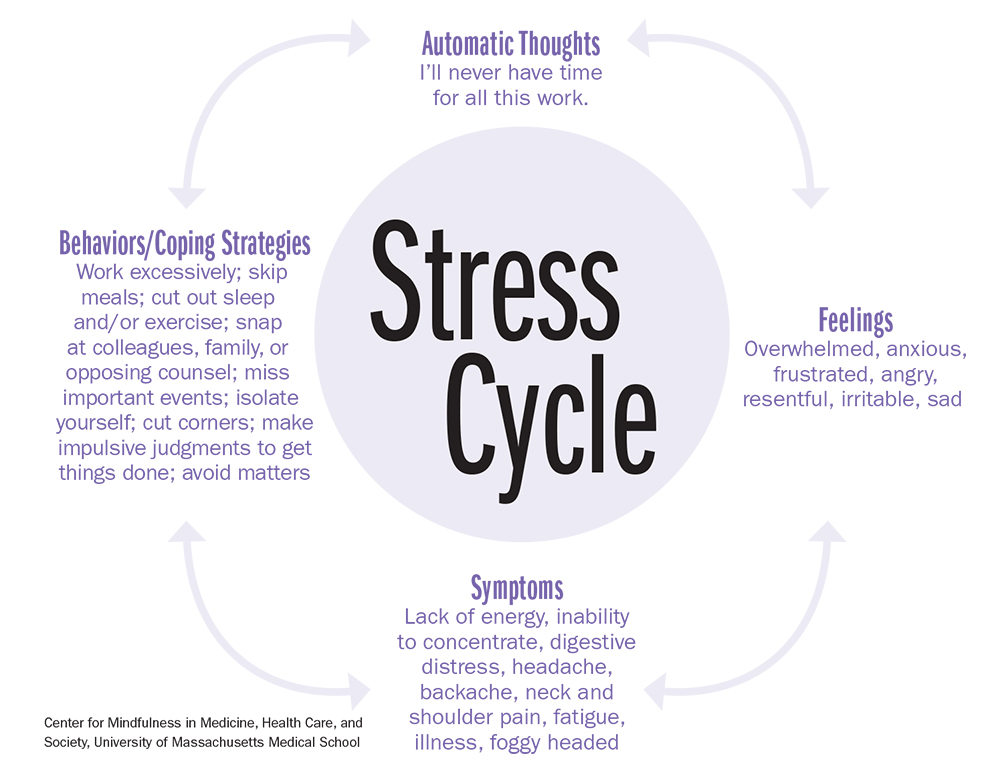

With awareness, we have a choice. We can notice our direct experience and then pause and intervene in the unhealthy autopilot thoughts and behaviors. Over time, we become familiar with our mental habits and how the stress cycle is activated. When I first began to practice mindfulness, I noticed that I have the following recurring thought: “I’ll never have enough time for all this work.” This is such a deeply wired thought pattern that it appears in my mind without any relation to reality. Take a look at the “stress cycle” diagram to see how that simple thought leads to an escalating cycle of stress. As we refine our ability to be aware of what is happening inside ourselves, we greatly increase our ability to intervene in any part of the stress cycle and make conscious and wise decisions about what is called for in the moment.

You might find it useful to consider some of your familiar negative thoughts and look at the chaos that ensues when you are not present to notice what is happening. Try the “STOP practice” to learn how to reduce the harmful impacts of stress.

The STOP Practice

As soon as you notice that you are having a reaction to something or someone:

Stop. Intentionally take a pause from current thoughts and activities.

Take a breath—or two or three, which is generally all it takes to connect with the present moment.

Observe. What is happening with you right now? What sensations can you feel? What emotions are present? What thoughts are going through your mind? What urges and behaviors are you noticing?

Proceed. The pause allows you to notice conditioned and automatic reactivity and to become more fully aware of the direct experience of the moment. If you can step out of autopilot, you have a choice about how you want to relate to the situation. Notice whether by adding space for awareness, your experience is different from in the past, and if you feel more able to respond skillfully rather than react in habitual knee-jerk ways.

The ability to choose more skillful responses in any situation is strengthened by formal mindfulness practice, such as the body scan. You can also practice informally during the day. You don’t have to add anything to your task list. All you have to do is pay attention to what you are already doing. Experiment, and see where you can fit in consistent and regular practice.

Here are some suggestions for mindfulness practices during a regular workday. Pick one, and try it for a week.

- Once you get to your office, take a moment to "just be." Become aware of your breath, feel the chair and your feet on the floor, and perhaps even name your intention for how you want to experience the day (not what you want to get done).

- Find two places in your day to integrate a mindful pause to “come to your senses” and bring awareness to the present moment, breath, and body. Afterward, with distractions lessened, you might see more clearly and move into the next moment more strategically and calmly. This pause may be one minute to five minutes.

- As you walk around the office, practice mindful walking. For a few steps, bring full attention to the soles of your feet as they meet the floor. This simple practice will slow down the frenetic mental and physical pace that so often takes over.

- Center before you enter.” Before going into a meeting or answering the phone, take a few breaths; feel your feet on the floor, your body in the chair, and your breath; and let go of what you have been thinking about and what you are going to do next. In this way, you bring your whole self to the conversation.

- Practice mindful listening. When you are in a meeting or conversation, notice the wandering mind and practice gently but firmly bringing it back to your breath and what is being communicated to you. Choose to listen purposely with curiosity and without judgment.

- Try single tasking. There is an inverse relationship between multitasking and productivity, accuracy, and efficiency. Research indicates that multitasking increases stress and can alter brain tissue and structure.16 Also notice how often you distract and interrupt yourself, and train yourself to stay focused on your intention.

- Check in with yourself from time to time throughout the day, allowing yourself to notice and intervene early if an inner storm is brewing. A good time to do this is during transitions from one task to another.<

The practice of mindfulness allows us to more skillfully respond to the inherent stressors and complexities of work and life—and to relate to whatever arises in our lives moment to moment in new and more satisfying ways.

Brenda Fingold, a former litigator, is a mindfulness-based stress reduction teacher and the manager of community and corporate programs at the Center for Mindfulness at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. She can be reached at brenda.fingold@umassmed.edu. Copyright © 2018, Brenda Fingold and Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society, University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Notes

- See Patrick R. Krill, Ryan Johnson & Linda Albert, The Prevalence of Substance Use and Other Mental Health Concerns Among American Attorneys, 10 J. Addiction Med. 46 (2016).

- Jim Loehr & Tony Schwartz, The Making of a Corporate Athlete, Harvard Bus. R. (Jan. 2001), https://hbr.org/2001/01/the-making-of-a-corporate-athlete.

- Id.

- Id.

- Am. Bar Ass’n, Compassion Fatigue, www.americanbar.org/groups/lawyer_assistance/resources/compassion_fatigue.html.

- Patrick R. Krill, Ryan Johnson & Linda Albert, supra note 1.

- Mindful, Jon Kabat-Zinn: Defining Mindfulness (Jan. 11, 2017), https://www.mindful.org/jon-kabat-zinn-defining-mindfulness/.

- See, e.g., Britta K. Hölzel et al., Mindfulness Practices Leads to Increases in Regional Brain Gray Matter Density, 191 Psychiatry Res. 36 (2011).

- Id.; Tom Ireland, What Does Mindfulness Meditation Do to Your Brain?, Sci. Am. (June 12, 2014), https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/what-does-mindfulness-meditation-do-to-your-brain/.

- See, e.g., Britta K. Hölzel et al., Stress Reduction Correlates With Structural Changes in the Amygdala, 5 Soc. Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience 11 (2010).

- Matthew A. Killingsworth & Daniel T. Gilbert, A Wandering Mind Is an Unhappy Mind, 330 Sci. 932 (2010).

- Brenda Fingold, Beyond Knowledge and Good Intentions: The Role of Mindfulness in Effective and Ethical Lawyering, Law Journal Newsletters (June 2017), https://tinyurl.com/yd8wyqrs.

- See Tony Schwartz, Take Back Your Attention, Harvard Bus. R. (Feb. 9, 2011), https://hbr.org/2011/02/take-back-your-attention.html.

- Jon Kabat-Zinn, Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness (Bantam 2013).

- Daniel Goleman, The Brain and Emotional Intelligence: New Insights (2011).

- See, e.g., Kep Kee Loh & Ryota Kanai, Higher Media Multi-Tasking Activity Is Associated With Smaller Gray-Matter Density in the Anterior Cingulate Cortex, PLoS One (Sept. 24, 2014).